Students will be introduced to the concept

of electricity by watching a short video with a catchy tune that will

have them looking for similar examples of electricity right in the

classroom. Extend this activity to walking through the school and

noting all the uses of electricity. For homework, ask students to

make a list when they go home. Several fun activities engage students

to consider what is meant by an electric circuit and how electrons

flow through wire as either open or closed circuits. Then students

will have the opportunity to explore how a flashlight works by taking

it apart and drawing the components and then lighting the bulb and

putting it back together. Through this activity, students will

experiment with lighting bulbs and learn the difference between

simple series and parallel circuits.

Part 1: What Is Electricity and What Is

Meant by Open and Closed Circuits?

Review what students know about electricity

as a form of energy from previous lessons (i.e., Where do we get it

from? Is it kinetic energy? It is potential, or stored, energy like

batteries? How do we use it?).

Turn on various electrical devices in the

classroom (CD player, light, TV, etc.) Ask students to give other

examples of electricity they see in the classroom or in their homes

and how the devices are able to work. Once students give “energy”

as the answer, ask them to define it. Energy is defined as the

ability to do work or make a change.

If time allows, take a walk through the

school and write down all the appliances, devices, machines, etc.

that use electricity.

Have students stand in a circle, close

enough to pass items from one student to the next but far enough

apart that just their hands touch. Give each student a ball (e.g., a

tennis ball). Explain to students that they have to pass the balls

from one person to the next with each person only holding one ball at

a time. Give students time to complete the task.

Remove one student from the circle and ask

students to pass the balls as before. They should not be able to

complete the task due to the open space. Collect balls and have

students remain in the circle.

Ask students to use different words to

describe the two different scenarios. Make a list on the board and be

sure that “open” and “closed” appear on the list.

Now tell students they are going to pretend

their arms are the wires that carry electricity. Have them touch

palms to complete the circle.

Ask two students next to each other to stop

touching each other and ask students if the current is open or

closed. Now have the two students each hold one end of a metal strip.

Now ask if the current is open or closed.

Explain that the metal strip is a conductor

and as long as each student is touching the metal “switch,”

electricity can flow. If the switch is turned off, by one student

letting go of the metal strip, the current will stop or is open so

that electricity cannot continue to flow.

Wrap up the activity by explaining open and

closed circuits and emphasizing two things that are needed: a power

source and a complete circuit. Explain to students that wires in a

circuit that connect objects (like switches, light bulbs, buzzers,

etc.) must start and end at the power source before they can work.

That’s why batteries have a top and bottom (+ and −) so they can

carry the charge all the way around.

Part 2: How Do I Light a Bulb?

Before starting this activity, ask students

what they would purchase if they were asked to go to the store and

buy a pound of electricity. Ask them to think for a minute and then

share their answer with their partner. Then ask for volunteers to

write their answer on the board. If they answer “light bulbs,”

ask if that means light bulbs are electricity. Or is it to say that

light bulbs work using electricity? This is a good opportunity to

correct misconceptions about electricity and reinforce the concept

that electricity is not matter. You cannot hold it in your hand

because it is a form of energy and does not have mass or volume like

matter.

Break students into pairs and give them a

flashlight. Ask if any of them have ever opened a flashlight before.

Ask students to take the flashlights apart and take the inside parts

out (spring, battery, bulb). Caution them about the breakable parts

and to hold the flashlights over their desks in case these parts fall

out. Have students draw and label the parts of the flashlight in

their journals.

Without giving directions, ask students to

light the bulb with only the parts that they removed from the battery

casing. To ensure success and lessen frustration, the teacher can

strip the ends of the wire with a wire stripper. Provide assistance

as needed. Ask students why they think removing the plastic coating

from the wire is important to solving the problem of lighting the

bulb. Ask students to experiment and raise their hands once they

light the flashlight. Instruct students to keep secret for the moment

how they were able to light the flashlight. Instead have students

draw a picture of what they did in their science journals while the

other students complete the task.

Allow students to visit with other groups

and try several ways to get the bulb to light. Ask students to draw

ways that work and ways that do not work. Now ask students to use

both batteries and the wire to light the bulb. It may be tricky but

they will notice the bulb is much brighter now. Have students

reassemble the flashlights and turn them on. Compare the brightness

of the bulb now with the brightness when they lit the bulb outside

the flashlight with the same two batteries. They should find them to

be identical. Ask students to write in their journal what they have

discovered, or any rules they established about getting a bulb to

light.

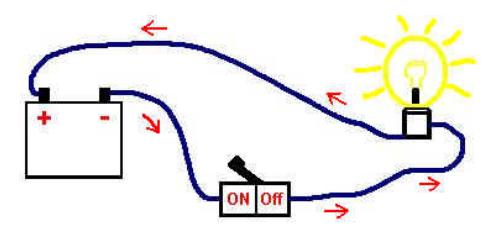

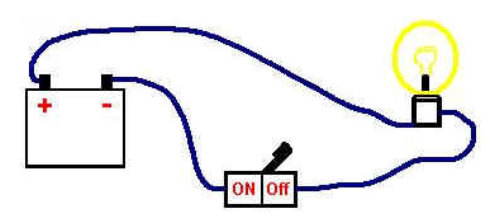

Discuss as a class how to light a bulb and

explain why it must be a closed circuit. Explain when you flip on a

light switch, you are actually closing or completing the circuit. A

circuit is the path that electricity flows. When you flip the light

switch off, you are opening the current and the light turns off

because the electrons cannot flow.

Ask students to show their drawings of their

completed circuit. Are they alike or different? To simplify drawing

circuits, there are common symbols to illustrate each part. Show

students the symbols for drawing circuits. Hand out the Electrical

Symbols Chart (S-4-5-3_Electrical Symbols Chart.doc) to each student. Using the symbols for batteries, wire, and a

bulb, draw a simple circuit based on what students just did to light

the bulb.

Now pass out switches and bulb holders to

each pair of students and have them light the bulb using the switch.

Take a moment and compare these materials to the ones they used to

light the bulb in the flashlight. Now draw the simple circuit using

these two new symbols. Ask a student to draw it on the board or

overhead projector. Have students check their work.

Wrap up the activity for the day by

reviewing what is necessary for a light to work in a house or

classroom. Ask students to think about if and how the simple circuits

can handle more than one light at the same time.

Part 3: What is a Simple and a Parallel

Circuit?

Review the activity from Part 2. Discuss

with students what one must have to light a bulb and a simple

circuit. Ask them how many bulbs they were able to light in the

previous activity. Now challenge them to see how many bulbs they can

get to light using their knowledge of circuits from the previous

activity.. Have students draw their setup once they light as many

bulbs as they can. Who could light the most bulbs at one time on the

same circuit? After applauding their efforts, ask them to draw the

setup and label the parts using the new symbols. Ask students how

they should label the pathways connecting the batteries, wires, and

bulbs. When they say “circuit,” write it on the board and define

it as a complete pathway from one end of the battery through the wire

and bulbs to the other end of the battery and through the battery

again. “This is that continuous pathway for the tiny charged

particles called electrons that flow through the wire and carry the

electric current.” Sketch together the circuit students

constructed and label the parts. Students should have the same in

their journals.

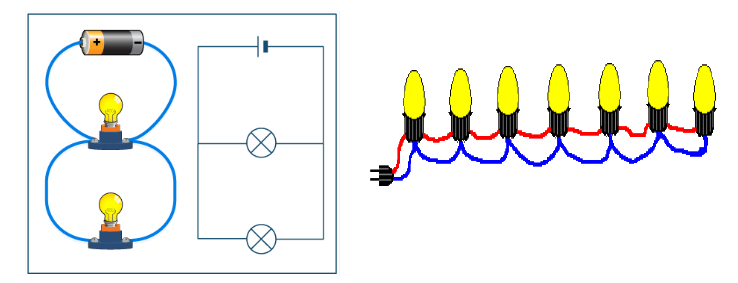

Example of a sketch with information:

The battery pushes electrons from the

negative terminal (where there are many electrons), through the

switch, the light bulb, and the wire into the positive terminal

(where there are not many electrons). As electrons pass through the

wire and into the light bulb, a special kind of wire inside the bulb,

called a filament, lights the bulb.

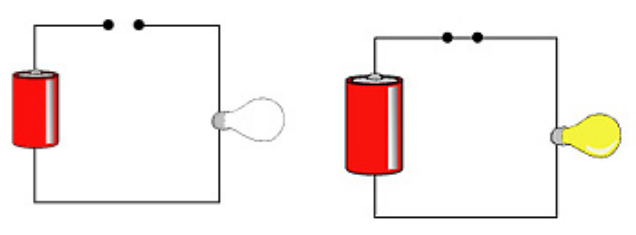

The circuit has been broken. The light bulb

is not lit. The flow of electrons has stopped because there is a gap

in the circuit, and the electrons no longer have a closed path.

Discuss as a class how many bulbs were lit

on one circuit. What did students notice about the light bulbs? (The

more you add, the less bright they become.) “Why is this?” (Each

bulb draws on the energy source and they become dimmer and weaker.)

“There are two basic ways in which to connect more than two

objects that use electricity: series and parallel.”

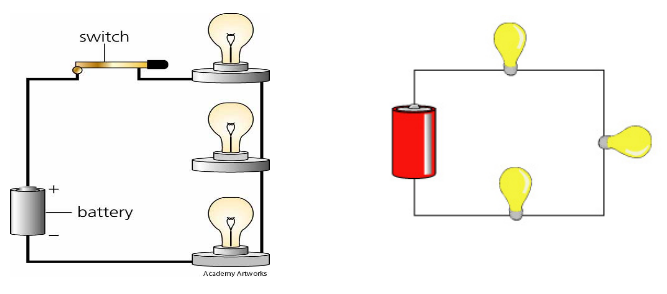

A series circuit has only one path for

electrons to flow. Components are end to end in a line forming a

single path. Ask students if they have put lights on a tree, and when

they plugged in the lights, the lights didn’t work. If one bulb

goes out, they all go out. This is one of the disadvantages of series

circuits.

A parallel circuit may have multiple light

bulbs because it has more than one continuous path for electrons to

flow. Each individual path is called a branch. All components in

parallel circuits connect between the same set of electronically

common parts, or in other words they are connected across each

other’s loads.

Have students work in pairs and try to build

a parallel circuit. How many paths and bulbs can they wire with one

battery? Have students draw their parallel circuits and demonstrate

them to the class. Discuss the results and use the Series and

Parallel Circuits handout (S-4-5-3_ Series and Parallel Circuits.doc) as a reference.

Series Circuits

A series circuit allows electrons to follow

only one path. All of the electricity follows path #1. The loads in a

series circuit must share the available voltage. In other words, each

load in a series circuit will use up some portion of the voltage,

leaving less for the next load in the circuit. This means that the

light, heat, or sound given off by the device will be reduced.

Parallel Circuits

In parallel circuits, the electric current

can follow more than one path to return to the source, so it splits

up among all the available paths. In the diagram, some current

follows path #1, while the remainder splits off from #1 and follows

path #2. Across all the paths in a parallel circuit the voltage is

the same, so each device will produce its full output.

- Extension: